Drive I‑295 through South Jersey and you’ll see the signs of a region in transition. The highway, once a simple conduit between suburbs and city, now threads through a landscape reshaped by commerce, redevelopment, and shifting community priorities. Among the most telling indicators of this change are two locations of Cinder Bar, an upscale-casual restaurant concept that’s quietly redefining what it means to dine — and live — in South Jersey.

These restaurants aren’t just places to eat. They’re reflections of how land use, economic development, and neighborhood identity are evolving along the I‑295 corridor.

Restaurants as Regional Indicators

Restaurants are more than businesses — they’re barometers. Where they open, who they serve, and how they integrate with their surroundings all speak volumes about a region’s trajectory.

Cinder Bar’s model — seasonal menus, craft cocktails, and a polished but relaxed atmosphere — caters to a specific demographic: young professionals, families with disposable income, and suburban commuters who want quality without formality. These customers are concentrated in the suburban nodes that dot the I‑295 corridor, from the commercial ribbons of Route 73 to the town centers of Cherry Hill, Deptford, and beyond.

For planners and civic leaders, the arrival of concepts like Cinder Bar signals a shift away from convenience-based retail (think strip malls and big-box stores) toward experiential destinations that encourage longer visits, repeat traffic, and community engagement.

The “Stay Awhile” Economy

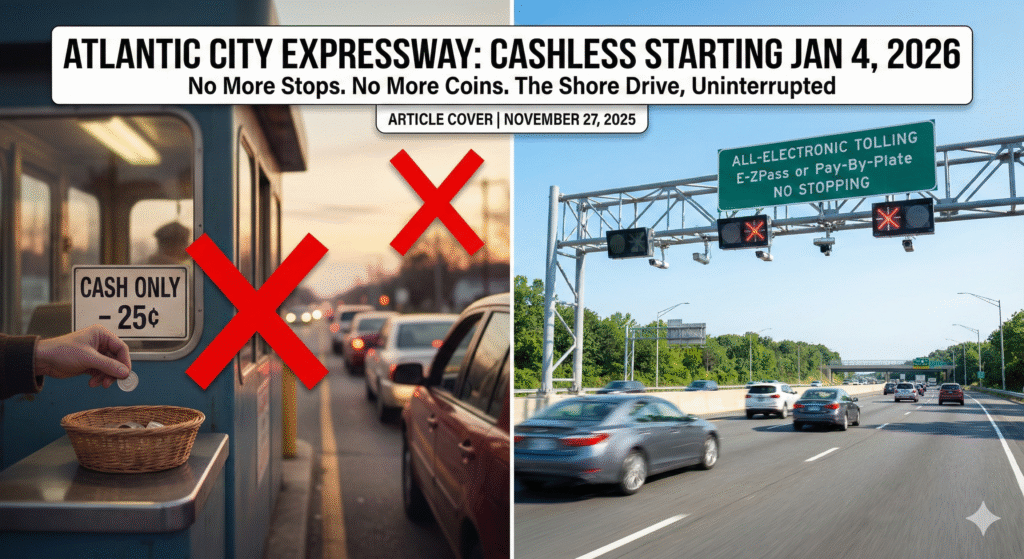

Cinder Bar’s locations are part of a growing trend: restaurants that serve as anchors for a new kind of suburban economy. Positioned near major roadways, they benefit from visibility and access — but they also contribute to traffic peaks, especially during dinner hours and weekend brunches. This matters in areas where infrastructure still prioritizes cars over pedestrians and transit.

When a restaurant becomes a destination, it creates ripple effects:

- A boutique opens next door

- A craft beer taproom follows

- A small performance venue finds an audience

These complementary businesses thrive in towns with mixed-use zoning, streetscape grants, and redevelopment incentives. Municipalities that embrace walkable, denser redevelopment — rather than single-story commercial strips — are best positioned to benefit.

Workforce & Small Business Ecosystems

Upscale-casual restaurants like Cinder Bar don’t operate like national chains. They rely on:

- Skilled kitchen and service staff

- Local vendors and purveyors

- Regional support services (cleaning, training, distribution)

When a concept opens multiple locations in the same region, it creates clustered demand — a potential opportunity for workforce development programs. Community colleges and municipal leaders can align hospitality training with employer needs, creating pipelines for living-wage jobs.

But there’s a flip side. Rising rents and property taxes can squeeze out legacy businesses — diners, bodegas, family-run shops. To avoid displacement, towns need deliberate policy:

- Small business grants

- Flexible lease models

- Commercial corridor stabilization programs

Civic Life & Cultural Anchors

Where a restaurant lands matters.

- Near a town center? It reinforces walkability and public space activity.

- Near a transit stop? It can justify better bus service and safer crossings.

- In a quiet residential zone? It reshapes social patterns — neighbors meet after work, families dine out locally after youth sports.

Civic leaders should ask:

Does this restaurant complement nearby cultural anchors?

Examples include:

- Cooper River Park

- Voorhees Town Center

- Haddonfield Historic District

These synergies can turn a restaurant into a community hub, not just a commercial tenant.

What Municipal Leaders Should Watch

To maximize the benefits of new dining destinations like Cinder Bar, towns along I‑295 should monitor:

- Infrastructure strain: Evaluate traffic flow near commercial clusters. Small upgrades — signal timing, turn lanes, pedestrian crossings — can prevent congestion.

- Zoning alignment: Ensure zoning supports mixed-use development and right-sized parking. Shared lots and infill projects promote walkability.

- Workforce pipeline: Partner with colleges and workforce boards to offer hospitality certifications tailored to local employers.

- Small business protections: Launch grant and loan programs to help legacy businesses adapt and compete.

- Transit connections: Advocate for better bus frequency and stop amenities to reduce car dependence and support evening activity.

A Living Record, Not a Prediction

Cinder Bar’s two South Jersey locations aren’t just new restaurants — they’re invitations. Invitations to shape how suburban life evolves along the I‑295 corridor.

Will these openings become part of a broader vision — walkable, mixed-use centers with thoughtful infrastructure and equitable growth? Or will they remain isolated amenities, surrounded by car-first corridors and rising costs that leave long-time residents behind?

The answer depends on intentional planning, community engagement, and a commitment to inclusive development.